- The Owen Wister Cabin on the old R Lazy S. Jackson Hole Historical Society & Musuem

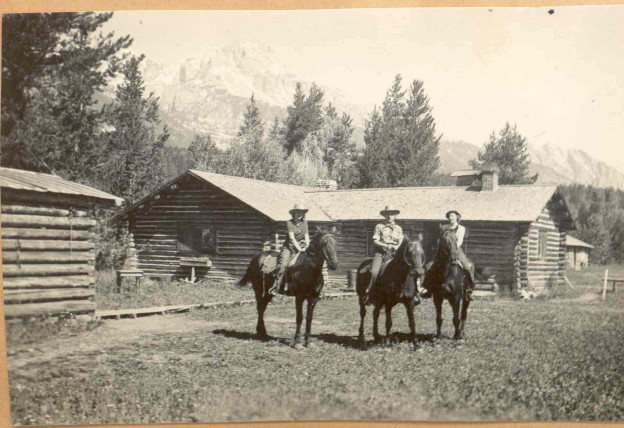

- The old R Lazy S Ranch. Courtesy of Carin McConaughy.

- The old R Lazy S Ranch gate. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

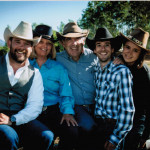

- The McConaughy Family. Courtesy of Carin McConaughy.

- The old Aspen S Ranch main lodge. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

- The R Lazy S Ranch gate. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

- The McConaughy family. Courtesy of Carin McConaughy.

- Claire and Bob McConaughy with Cara and Howard Stirn. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

- Howard and Cara Stirn with grandsons Matthew and William. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

- Kelly and Nancy Stirn. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

- Angel hears a secret from Matthew Stirn. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

- A pack trip returns to the ranch. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

- The Stirn Family in 2016. Courtesy of the R Lazy S Ranch.

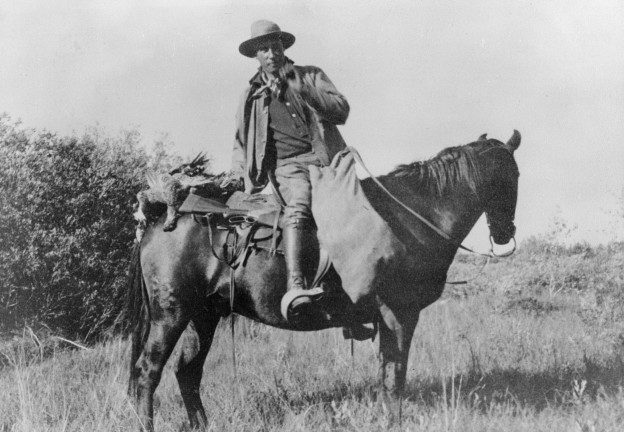

In 1910, Elsie M. James (née Olsen) received Homestead Patent #145265 for 151.33 acres along what is now known as the Moose-Wilson Road. The homestead was located just north of the White Grass Ranch Road. At the time the patent was given, the White Grass wouldn’t be created for another three years. This would have been a very quiet piece of land, with only the beginnings of the JY Ranch about a mile south. Just a year later in 1911, Mrs. James sold her homestead to Owen Wister. The Wister family was looking for a private homestead of their own after staying at the JY Ranch. The Wisters built their own cabin on the property in 1912. There are rumors claiming that Wister wrote his famous The Virginian here. Unfortunately the dates do not add up, as The Virginian was published in 1902. The cabin remained on the property until 1974 when Grand Teton National Park arranged for it to be dismantled and reassembled in Medicine Bow, Wyoming. It remains there today, part of the Medicine Bow Museum.

The Wister family’s time here was tragically cut short when in 1913, Mrs. Wister died from childbirth complications. Owen Wister did not return to the Jackson Hole cabin, but he did retain ownership until 1920 when he sold the land to the Roesler, Laidlaw, and Spears families. These three families developed the land into a private family retreat, naming it the R Lazy S Ranch for each of their surnames. In 1928, Chauncey Spears added an additional 40 acres through a homestead patent. This would have been one of the last patents awarded in Jackson Hole. In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge issued Executive Order #4685, effectively closing much of the remaining public lands in Jackson Hole to homesteading. The RLS families built some of the main ranch infrastructure and maintained the property until they sold it to Robert and Florrelle McConaughy in 1946.

Robert and Florrelle began renovations to open the property as a dude ranch. Some cabins needed updating and others needed to be expanded to provide enough room for guests. The next summer in 1948, the McConaughys opened for their first official season; they first appeared in “Dude Ranches Out West” in 1949. This booklet was printed by the Union Pacific Railroad to entice travelers to utilize railroads in their family vacations to the “wild west.” Robert and Florrelle took an unusual step in their cabin renovations in that they added electricity and plumbing with hot water. Most dude ranches did not provide these modern amenities, believing that part of the appeal of the western vacation was the rustic accommodations. They could house up to 40 dudes and kept the operations small intentionally. The McConaughys had been guests of the nearby Bear Paw Ranch and understood the appeal to having a smaller, more intimate dude ranch. Fewer dudes allowed for a more personalized experience. The guests could connect better with each other and the owners, creating a family-like atmosphere.

Robert Sr. and Florrelle had two children, Robert Jr. (Bob) and Geraldine (Shonnie), who both lived and worked on the ranch. In 1953, the land was sold to Grand Teton National Park under a lease lasting twenty years. This was just three years after the last expansion of the park in 1950 to its current borders. It was ten years after the Jackson Hole National Monument was formed in 1943, which included the land surrounding the R Lazy S. The land was in a valuable location on the northern portion of the Moose-Wilson Road, with Snake River frontage; its stunning views of the Tetons was the primary reason that the property was sought after by the park. Bob and his wife Claire would take over operations after Bob’s father died in 1963.

Bob and Claire inherited a well-run ranch in 1964 and had few modifications and remodeling to do. They kept numbers at 40-45 dudes and many of the original families continued to come. Leading up to the last year of the lease, the Snake River was threatening to flood the property. Help came in the form of a unique partnership with previous ranch guests who wanted to preserve the community and character of the R Lazy S. Howard and Cara Stirn were former R Lazy S dudes who had acquired their own Jackson Hole ranch, just four miles south. In the winter of 1972, ten buildings were moved down the Snake River dike to the new location, and the next summer the R Lazy S was re-opened. Bob and Claire had two daughters, Carin and Kim, who lived and worked on the ranch. In 1975 the McConaughy-Stirn partnership was made official when the Stirns purchased the ranch operation and the McConaughys continued to manage daily activities. This arrangement was kept until Bob’s death and Claire’s retirement in 2002. The McConaughy name is still connected to the ranch through their daughter Carin, a wrangler.

Bob was also active in the Jackson Hole Rodeo, purchasing the contract with partner Hal Johnson from 1969-1979. After a brief hiatus, Bob again held the rodeo contract from 1987-1993. He traveled around the country finding the best rodeo horses, reveling in their wild spirit. It was during one of these trips to Cedar City, Utah that he happened upon an abandoned donkey, who he intended to use a pack animal. Upon her arrival to the ranch, Angel was met with some skepticism over what a dude ranch could possibly do with a donkey. Her use as a pack animal was short-lived, hard labor was not in her wheelhouse. Undeterred, Bob insisted that there was a place for Angel at the R Lazy S, and she quickly won over every guest and crew member with her sweet temperament. She became the self-appointed sentinel of the barn and the “most photographed” animal on the ranch. Angel experienced no lack of love and treats during her 25 years on the ranch. After a full life keeping the ranch in order, Angel passed away in the fall of 2014. Her years in service at the ranch rival those of any of her human counterparts.

Cara Stirn initially came out to Jackson Hole with her parents, Kelvin and Eleanor Smith, and sister Lucia to stay at the Bear Paw Ranch in the 1940s. Cara later married Howard Stirn, and they had Bradley, Lucia, Kelvin, and Ellen. Cara would return to Jackson Hole after her daughter Lucia came to the Teton Valley Ranch Camp in the early 1960s. They stayed at the R Lazy S after they retrieved Lucia and the family fell in love with the valley. The Stirns would return annually when their son Kelvin also discovered the Teton Valley Ranch Camp. Howard and Cara eventually decided that they wanted to own their own ranch in Jackson Hole. They discovered that Cara’s parents already had land in the valley that had been surveyed for a potential 60-house subdivision. Kelvin Smith (Cara’s father) knew he wanted to save the land from development and purchased it. He then sold it to Howard and Cara in 1972, for use as a family ranch. It had initially been called the Aspen M Ranch, for the Mosley family. Previous landowners included the Linns, Colbrans, and Hansens. The Stirns would eventually acquire 323 acres, renaming it the Aspen S Ranch. Robert Goulet of Camelot fame was a neighbor, and family friend, who sold the Stirns 40 acres in 1978. Howard and Cara were early advocates of conservation in the valley, and became the first to donate their land to the Jackson Hole Land Trust in 1981. Today the ranch is owned in part by the Land Trust, R Lazy S, Aspen S and Stirn family.

The Aspen M Ranch buildings were incorporated into the Aspen S and later R Lazy S ranches. The most prominent were the lodge and barn, along with the caretaker’s cabin. The tack sheds, Spruce, Sage, Rendezvous, Aspen S, and Rafters cabins were all already located on the ranch. The R Lazy S cabins that were moved to the property were the Main Office (formerly McConaughy), Teewinot (Laidlaw), Teton, Willows, crew bathhouse, dorm, Gate and Little Mac. The Stirns and the McConaughys operated the ranch in a unique partnership that lasted for thirty years. Some of the cabins on the ranch have long histories that connect the ranch to the entire valley. The Crew Moc Shop was once owned by Ellen Walker, a locally famous women’s clothing shop owner located in the town of Jackson across from the Wort Hotel. The housekeeping shed was once located at Stephen Leek‘s (nationally renowed for his work saving the wild elk population in Jackson Hole) Lodge (today Leek’s Marina). A crew cabin came from the old Alpine Motel in Jackson.

Kelvin “Kelly” and his wife Nancy were living in California when they decided to return to the R Lazy S and build a summer home. Shortly afterwards, they moved to the ranch full time with their sons Matthew and William. Kelly began taking over more of the ranch duties, until he and Nancy became Directors in 1997. Howard and Cara continued to be involved with guest operations and hosting duties. In 2012, Kelly and Nancy assumed full ownership of the ranch.

The ranch still houses 40-45 dudes, to retain the small community atmosphere. The ranch is designed to facilitate the optimal family experience; with activities geared toward the whole family, and some kids-only activities. The minimum stay is a week, however longer visits are encouraged. This originates from the early dude ranches that required a two-week minimum stay. The Stirns continue to welcome old and new generations of families to the ranch. The have a unique tradition of giving out belt buckles to families and individuals who reach certain milestones at the ranch. To date, they have given out 333 ten-year bronze buckles and 108 twenty-year silver buckles. The R Lazy S has a unique legacy of family and community. The perseverance of the owners, crew and guests to keep the ranch alive is something to be admired. The R Lazy S will celebrate its 70th year of operation in 2017.

Text by Samantha Ford, Director of Historical Research and Outreach