The Wilson Family left to right: John, Mary (mother), George, Mary Alice, Charles, Rebecca, Elias, Melvina c.1898. Not pictured: Sylvester (d. 1895), Ervin (d.1897) and Martha.

First Families is a unique exhibit dedicated to the first families who made Jackson Hole their permanent home. The entirety of the research and family photos have been collected by direct descendants of these families. Authored by Melvina Wilson Robertson, the story was an account of Sylvester Wilson and his family’s decision to move from Wilsonville, Utah to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Melvina was the 12th child of Sylvester and Mary Wilson, and she was three years old when these events unfolded. Even as a young woman, Melvina recognized the importance of preserving these details, many soon lost to time and the invention of modern technologies. She considered herself the family biographer and began keeping detailed notes and collecting family photos.

Upon her death in 1952, her large collections were kept intact and eventually passed to her granddaughter, Judith S. Andersen. It was Judith who passed copies of her family’s extensive records onto JHHSM, and many early details of homesteading in Jackson Hole are finally being retold. The true extent of Melvina’s research and the hundreds of extended family members she documented through genealogical records is too vast to share here. Three bound books containing her work are available upon appointment in the Stan Klassen Research Center.

What follows below is a first-hand account of what everyday life was like in the first wave of homesteading in Jackson Hole from 1890-1900. During these years, life in the valley was exceptionally isolated. There wasn’t even a clear route over Teton Pass; these first families felled the first trees to allow their wagons to pass. How they then built and illuminated their homes, how they dressed themselves and what they ate, how they survived the long winter months are all brought to light through Melvina’s writing. While many accounts and documents exist with this information, few are firsthand accounts written by the individuals who experienced this lifestyle.

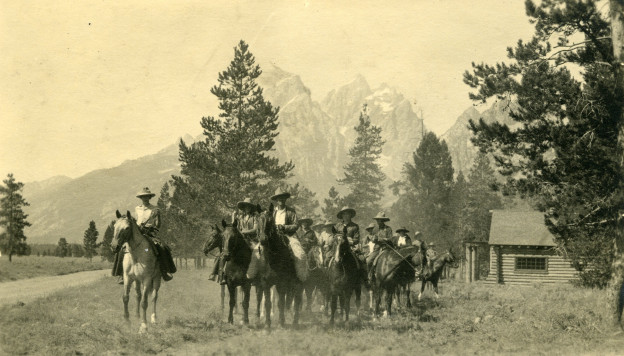

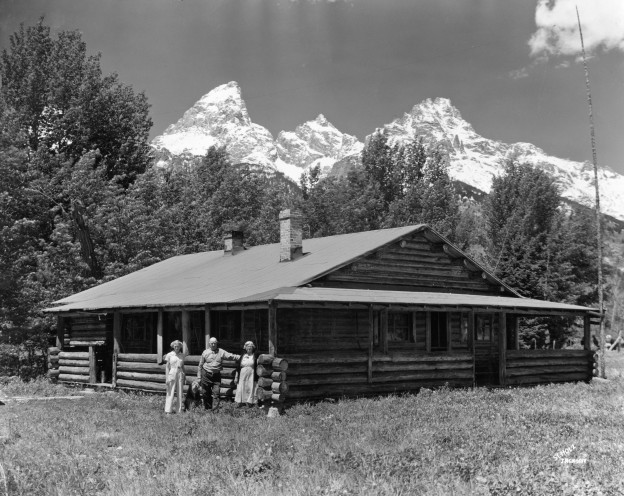

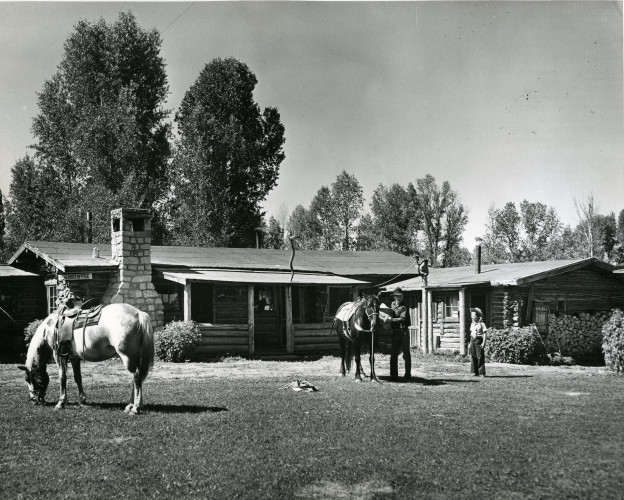

When the dude ranching boom hit in the 1920s, Jackson Hole was still rugged country, however it was very much on the map. Conveniences like kerosene lamps, regular mail service, general and grocery stores, and a rudimentary (but extant) road system allowed locals and dudes alike a comparatively comfortable life. Just twenty years prior, the first general store offering luxury items like flour, shoes, clothing, wash bins and candy opened in the newly-named town of Jackson in 1900. For the early homesteaders, a yearly trip was made over the treacherous Pass to Idaho that took weeks. By the time Melvina reached adulthood, convenience was just a day’s ride away, and what Pap Deloney couldn’t stock, the mailman could haul over the Pass.

What was it like to live and work on the first homesteads in Jackson Hole? Click on the photos below to find out!

Samantha Ford

Director of Historical Research and Outreach