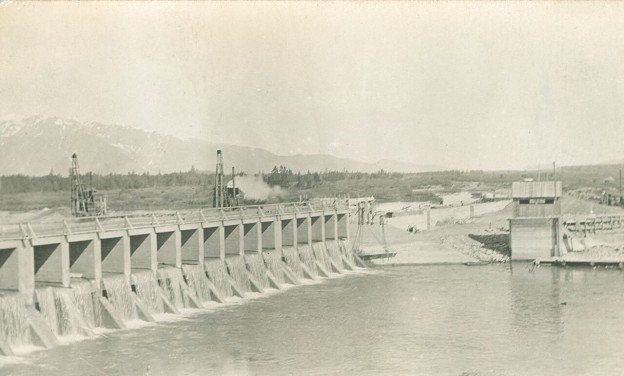

- Teton Lodge. From the collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum

- Teton Lodge reconstruction after 1910 fire. From the collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum

- Town of Moran. From the collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum

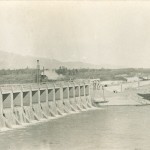

Captain Edward “Cap” Smith and his wife Clara were some of the first settlers in this region, prior to 1900. Frank Lovell had a homestead just next door. Cap and Clara Smith opened and ran a roadhouse when traffic started coming down the military road from Yellowstone in 1890-1892. It is thought that this modest two-story log structure burned around 1900. By the time Sheffield arrived and saw the area’s promise for a hunting lodge, the Smiths and Lovells were ready to move on. In 1903, Sheffield purchased both homesteads with the intention to open a hunting lodge. The area did not yet have a name, but it was already becoming a tourist “destination.” Many believe that it was Frank Lovell who was responsible for building the toll bridge that allowed access into Moran over the dam site. Other sources claim this was Ben Sheffield’s doing, after he built the Teton Lodge in 1903.

Located on the outlet of Jackson Lake, just below the future site of the dam, the lodge was a central location for many tourists travelling through Jackson Hole. In the early years Sheffield catered to wealthy hunters looking for guided trips into the Jackson Hole wilderness. This was a business he was skilled in, having previously led hunting trips in Livingston, Montana. In the fall he left for hunting and trapping, and in the winter he lived in Chicago, selling his pelts and working for an outdoor supply store. As his Teton Lodge continued to grow and he added more cabins, the business quickly grew to accommodate overnight tourists arriving from Yellowstone.

In 1906 Sheffield married Margaret Rice from Wisconsin. The two met in Moran when she was visiting with friends. She stayed on with Ben to help run the Teton Lodge. It was a large operation that took up most of the town of Moran. Sheffield had certainly picked a fortuitous site, as the Jackson Lake Dam construction projects brought a lot of cash and workers into the town. Construction also began nearby on the military camp for the Reclamation Service, turning the town of Moran into a bustling hub of activity. In 1907, Sheffield purchased the Moran post office from the Allens, and moved it to his Teton Lodge, and became postmaster on January 2, 1907. In 1925, he purchased the remainder of the Allen’s Elk Horn Ranch.

In 1910, Sheffield experienced a disaster that would be a major setback for his growing business. A fire destroyed the dining halls, kitchen, post office and his private living quarters. Later that year the log dam, the first dam to be built on Jackson Lake, failed and the town was flooded. The water was high enough that Sheffield purchased a boat and kept it tied to the front porch in case he needed to leave in a hurry due to rising water. This same flood washed out the toll bridge that allowed traffic to cross the dam area into Moran. Despite all this, Sheffield decided to rebuild rather than move on.

By the time the Sheffields sold to the Snake River Land Company in 1929, they were running a large operation that could accommodate 300 guests. This far surpassed the capacity of any dude ranch in the valley. The main lodge burned again in 1935, but the Teton Investment Company also rebuilt and continued to operate it until the 1950s. By 1959, the newly formed Grand Teton Lodge Company had moved most of the buildings in town to Colter Bay and other areas around the park. Some were torn down and removed. At this time, what was left of the town of Moran was physically moved to its current location, about 11 miles to the west. The old town site was re-graded and re-vegetated.

In 1955, with the construction of the Jackson Lake Lodge, the old ramshackle town of Moran was no longer an eyesore on the natural beauty of Jackson Lake. The Lodge was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 2003, which is the highest distinction a historic building can earn. The Murie Center in Moose is the only other National Historic Landmark in Grand Teton National Park. It is rare to have two such Landmarks in such close proximity.

TIMELINE

1903: Benjamin Sheffield purchases the Lovell and Smith homesteads and begins construction on his Teton Lodge.

1906: Sheffied marries Margaret Rice, and the two manage the Lodge.

1907: Sheffield purchases the Allen property that includes the Elk Horn Hotel, the Moran post office and a small mercantile.

1910: A disastrous fire followed by a flood nearly levels the Teton Lodge. The Sheffields decide to rebuild and create a successful Lodge capable of housing up to 300 guests.

1911-1916: Jackson Lake dam construction brings a lot of business into the Moran area.

1929: Sheffield sells his property, effectively selling the town of Moran to the Snake River Land Company. The Company, seeing the advantage of keeping the Teton Lodge open for tourists, hands management over to the Teton Investment Company. In the 1950s, this would transform into the Grand Teton Lodge Company which manages the Jackson Lake Lodge today.

1935: The Teton Lodge’s main building burns down.

1950-59: The Grand Teton Lodge Company moves most of the old Sheffield cabins up to Colter Bay. What can’t be moved is torn or burned down. The town site is re-graded and re-vegetated. Today, nothing remains of the original town of Moran.

1955: The Jackson Lake Lodge is constructed.

Text by Samantha Ford, Director of Historical Research and Outreach