FORCES THAT SHAPED THE LAND

The Tetons rising from the sage plains of the valley. Photo by Samantha Ford

“Over these seemingly changeless mountains, in endless succession, move the ephemeral colors of dawn and sunset and of noon and night, the shadows and sunlight, the garlands of clouds with which storms adorn the peaks, the misty rain-curtains of afternoon showers.” -Fritiof Fryxell, The Tetons: Interpretations of a Mountain Landscape, 1966

The Teton Range is one of the youngest mountain ranges in the country, yet it contains some of the oldest rocks. Due to geologic forces, the valley floor is sinking, causing the Tetons to rise slightly. This movement results in the distinctive look of the mountains which appear to be erupting directly up from the flat valley floor. Several periods of glaciation shaped the more prominent topographic features of the valley. Although the last glacial event ended around 12,000 years ago, clues can still be seen in the landscape today. Large continental glaciers covered the valley floor, while mountain glaciers extended down through the Teton canyons to carve out lakes such as Phelps, Bradley, Taggart, Jenny and Leigh, at the base of the mountains. Timbered Island, the Potholes and the vast sage flats are all evidence of glacial activity. Most of the valley is covered with plains of sagebrush, the result of a wide glacial river that washed away sand and silt to leave behind larger river stone cobbles. These cobbles are of mixed geologic origin and come from the several mountain ranges surrounding the Jackson Hole valley.

EARLY HUMAN HABITATION

Click on the image above for a full view. Visual courtesy of the archaeology collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

After the last major continental glacier receded, humans began to move into the valley. The earliest documented evidence of people in Jackson Hole are Folsom projectile points from the Paleoindian Period which date to about 11,000 years ago. Over the next several thousand years, many different indigenous groups would establish both campsites and transportation routes throughout the valley. These groups include but were not limited to: The Mountain Shoshone (also called Sheep-Eaters), Eastern or Plains Shoshone, Crow, Bannock, Blackfoot, Northern Arapaho, Gros Ventre and Nez Perce. Traces of their camps and transportation routes are still visible in the numerous archaeological sites on both the valley floor and in the high Tetons. These sites suggest that these groups used the valley seasonally, arriving in mid-May and following snowmelt into the mountains in late fall. They made good use of a wide range of the region’s abundant food sources, following herds of elk, bison or bighorn sheep. Berries, tubers, roots and nuts – especially pine nuts from the white bark pine tree – were also part of their diet. Archaeological evidence suggests and oral histories from the Shoshone confirm, that pine nuts would have been an important staple. Large family groups would have taken communal gathering trips into the mountains to collect and process this exceptionally nutritious form of fat and protein.

- Soapstone bowls. Soapstone (steatite) is soft and easy to carve. The bowls were used for cooking and serving food. Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

- Wikiup. Constructed with logs patched together with mud and grass for a shelter. Also called a Conical Timber Lodge. Photo courtesy of Matthew Stirn.

As technologies advanced in food processing and hunting, these seasonal populations expanded, as evidenced by the increased number of archaeological sites dating from later periods. Obsidian, a form of volcanic glass, became a popular material for all manner of tools. Because of its incredibly sharp nature and easy flaking properties, obsidian was an important resource, readily available locally, for producing spear points.

Atlatl: an ancient hunting tool used by Paleoindian and Archaic Period peoples. Courtesy of Alberta Culture and Tourism, Historic Resources Branch.

Soon the bow and arrow would replace the atlatl, an early form of throwing spear, as the primary hunting weapon. The sinew-backed bow, made from the horns of Rocky Mountain bighorn rams, is characteristic of the Shoshone and Crow Indians who used this area. Traded as far away as the Upper Missouri River valley, these incredibly powerful bows were recognized as the most powerful hunting weapon in North America prior to the introduction of European fire arms.

MOUNTAIN MEN AND FUR TRAPPERS

- David Jackson. Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum

- Jim Bridger. Photo courtesy of the Denver Public Library.

“Here we found a few Snake Indians comprising six men, seven women and eight or ten children, who were the only inhabitants of the lonely and secluded spot. They were all neatly clothed in dressed deer and sheep skins of the best quality and seemed to be perfectly contended and happy.” – Osborne Russell, Journal of a Trapper 1832

In the early 19th century, fur trappers eager to exploit one of the valley’s most valuable resources, beaver furs and other pelts, found their way into the remote valley of Jackson Hole. While the major centers of the fur trade were outside Jackson Hole, many significant routes passed directly through the valley. Towering over the Snake River and low valley, the Teton Range became an unmistakable landmark. According to one tradition the Tetons got their name from French fur trappers who noted their resemblance to large breasts. However, according to at least one Crow historian, the name derives from the Crow or Apsaalooke word for the mountains which sounds very similar to the French pronunciation of “Teton,” and translates as “pointed and jagged.”

The stone reportedly carved by John Colter in 1808.

John Colter, hunter and guide for the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806), is long thought to be the first Anglo-American to enter Jackson Hole. It is thought that his travels took him through the region of what is now Yellowstone National Park and probably along the shoreline of Jackson Lake during the winter of 1807-1808, however his route is disputed today. In 1933, farmers in Idaho unearthed a stone resembling a human face with the words “John Colter 1808” carved into it. Some believe this carved stone serves as evidence that proves Colter’s route through Yellowstone and Jackson Hole. Others believe the stone is a hoax.

Over the next four decades after the Lewis and Clark expedition, the fur trade continued to operate in the Rocky Mountain West. It would decline sharply after the early 1830s as beaver were virtually exterminated at this time. The disappearance of the beaver drastically changed the configuration of high country waterways, lakes and ponds. Originally sought after for men’s fur hats and other fashionable articles of clothing, beaver fur fell out of favor and only the changing tide of Eastern fashion prevented it from disappearing altogether. By 1840, the fur trade was considered to have ended. Many of the fur trappers found new work as guides for research expeditions through the Rocky Mountains. These men had spent years in this rugged country, and knew it well.

THE MOUNTAIN MAN RENDEZVOUS

“I defy the annals of chivalry to furnish the record of a life more wild and perilous than that of a Rocky Mountain Trapper” -Francis Parkman

Jackson Hole resident with furs. Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum

Mountain men like David Jackson (for whom the valley is named), Jedidiah Smith, Jim Bridger and William Sublette would become synonymous with this rugged and isolated lifestyle. Wilson Price Hunt, in the employ of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, led a group of trappers up Wyoming’s Wind River in 1811 and over what is now called Union Pass, crossing the Continental Divide and then heading down the Hoback River to its confluence with the Snake. The sight of the three most prominent peaks of the Teton Range cheered the company on:

“Here one of the guides paused, and, after considering the vast landscape attentively, pointed to three mountain peaks glistening with snow, which rose, he said above a fork of the Columbia River. They were hailed by travelers with that joy which a beacon on a seashore is hailed by mariners after a long and dangerous voyage.” –Wilson Price Hunt, Overland Astorian, 1811.

While often portrayed as romantic figures, glorified for their skills in surviving in harsh and unforgiving terrain, in reality this occupation was extremely hazardous, and scarcely ever yielded a decent living. Trappers working alone or with a small group of partners were subject to attacks by hostile Indians, grizzly bears and other wild animals, often in arduous and dangerous conditions. Trapping took place in the fall and in the early spring when beaver pelts were at their most luxurious and desirable in the long cold months of winter. Often alone for months at a time, they would come together in the summers to sell their furs at outposts of some of the region’s major fur companies at trade gatherings called “rendezvous.” The rendezvous tradition of trading and selling furs was started in 1825 by General William Ashley’s men of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company – many were held in Wyoming’s Green River country, near Lander, WY, along the Utah and Idaho border, and Pierre’s Hole in Idaho.

THE RAYNOLDS EXPEDITION OF 1860

During the period of 1840 after the end of the fur-trapping era, until 1860 there is little documented use of the valley. The next group to enter Jackson Hole came under Captain W.F. Raynolds’ military mapping expedition, guided by veteran mountain man Jim Bridger. The reports of the beautiful and wild natural resources in western Wyoming during the fur-trapping era had not gone unnoticed by the U.S. Government.

“The objects of this exploration are to ascertain, as far as practicable, everything relating to the numbers, habits and disposition of the Indians inhabiting the country, its agricultural and mineralogical resources, its climate and the influences that govern it, the navigability of its streams, its topographical features, and the facilities or obstacles which the latter present to the construction of rail or common roads, either to meet the wants of military operations or those of emigration through, or settlement in, the country.” –War Department, Office Explorations and Surveys, 1859.

The next wave of visitors to the valley would be in the form of Government survey parties sent to evaluate the natural resources for their potential economic value. Several expeditions would trace routes through Jackson Hole until the U.S. Geologic Survey was founded in 1879. The “age of discovery” in America is considered to have ended at this point.

MINOR PROSPECTS

Mining operation in Jackson Hole. Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum

It was during the time of exploration in the valley that news also spread east about the wealth of resources in the west, namely precious metals. Prospectors and miners began their journeys west on the heels of the explorers and scientists. Several prospecting attempts were made in Jackson Hole, however many ended up fruitless. Minor traces of gold led to conflicting reports about the mining success in the valley and nearby regions. In 1870 there was a modest rush in the Wind River Range due to false reports. Few mining operations in Jackson Hole were successful, however the locations of the claims were closely guarded. Conflicting reports remain as to the total success of mining in the valley. The Whetstone Mining Company was founded on Whetstone Creek in the Teton Wilderness in 1889. The company built cabins, sluices, a sawmill and even a ferry. By 1897, the operation was shut down. Prospectors never found any fortunes in the valley, where small traces of gold were located, Jackson Hole was no match for the success of California and other areas of the west.

EARLY SETTLERS TO THE VALLEY

A homestead near Moran. Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum

“When we were little kids and lived in those old log houses the wind howled right through those cracks! It blew so hard that our folks would have to keep an eye out to bring us back across the room where we’d been playing!” –Clark Moulton, Legacy of the Tetons

Despite the misfortune of the prospectors, the valley began to be settled by permanent residents around 1884. The first two Anglo-Americans to take up fulltime residence in the valley were John Carnes and John Holland. They filed for adjacent homesteads on the south end of today’s National Elk Refuge. Over the next decade, the homesteader population rose from 23 to 639 by 1900. By 1920, these numbers would more than double to 1,381 residents. These numbers only account for those living legally on the land, and those who participated in the government census. Homesteading was possible in the west through a series of Homestead Acts designed to encourage settlement through free land acquisition. The U.S. Government would grant 160-acre plots to those who qualified for the application process and paid a small fee of $10-15. A homesteader was an individual 21 years or older, the head of a household and someone who had never taken up arms against the United States government (the Civil War was in its first year when the Act was signed – the war ended in 1865.) Even women were allowed to file for a patent, providing she was single.

Cattle on the Jackson Town Square. Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum

Homesteading in Jackson Hole was a careful balance of surviving the harsh winters, short growing season and unexpected, violent weather patterns. Droughts, mid-summer hail storms and even the wildlife posed serious threats to the livelihoods of homesteaders who tried to raise cattle or hay. For many in Jackson Hole, 160 acres was simply not enough land to raise both cattle and the amount of hay needed to keep livestock and horses through the winter. Many were able to file for adjacent tracts through another Homestead Act, and others bought out neighbors who found the conditions too challenging. The many who persevered took great pride in their ranching operations, knowing they were solely responsible for their success. Some took creative routes to supplement their income, taking jobs with the Forest Service, or the Reclamation Service reconstructing the Jackson Lake Dam. Women ran the local post office, or taught at the small community schools to help make ends meet. Many ranchers found a new source of income in the increasing number of tourists traveling through the valley to see Yellowstone National Park. By offering a bed and food to the weary travelers, the ranchers began to rely less on cattle and haying operations.

THE DUDE RANCH COMES OF AGE

Dudes Branding a Horse. Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum

“Dude ranches boasted a classless society full of class, where the swagger of Western horsemen blended on equal terms with the swagger of adventurous, anti-conventional Eastern aristocracy. Everyone—ranchers, Jackson storekeepers, hired hands, dudes—were caught up in this society, involved in the intense feuds and friendships, the bitter causes (park extension and related problems), took sides, cheated on each other selling horses and playing poker, loved, hated, even married each other.” – Nathaniel Burt, A Classless Society: Dude Ranching in the Tetons 1908-1955

The overnight travels of early tourists quickly evolved into stays lasting weeks at a time. Dude ranching was a natural progression in Jackson Hole from cattle ranching. For many, wrangling dudes brought in more income and relieved the economic pressures which too often resulted from the unreliable weather. Many dude ranches continued to run cattle in an effort to bring in more visitors with the lure of staying on and participating in the life of a genuine “working cattle ranch.” Dudes would arrive in late spring, and stay throughout the summer, departing in early fall when the ranches closed for winter. Several dude ranches would also host big game hunters during the late fall months. With the picturesque mountains, sage brush plains and winding rivers ideal for fishing, Jackson Hole became a sought-after vacation destination. From 1908 when the first dude operation in Jackson Hole opened at the JY Ranch, until 1929 and the Great Depression, the “golden age” of dude ranching was at its peak in the valley. Hundreds of dudes would visit the valley in the summer months, often out-populating those who lived in the town of Jackson year-round.

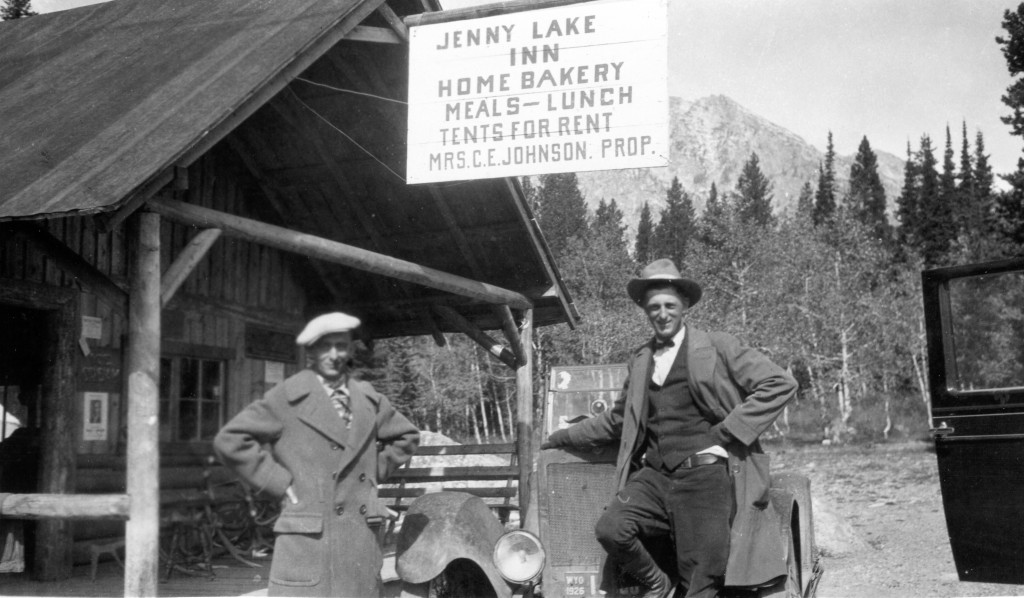

CHANGES IN TRAVEL AND TOURISM

“[The tourists] often ask, ‘Where’s Slippery Lake?’ So we’d show them how to get on up to Slide Lake. They’ll say, ‘How long have you lived here?’ We’ll answer, ‘Quite a while, our grandparents homesteaded. The Tetons were just little fellows when we come in. We watched ‘em grow up!’” –Clark Moulton, Legacy of the Tetons

- Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum

- Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum

After the Depression and two world wars, vacations were changing in American society. With the advent of affordable family automobiles, railroads were quickly falling out of favor as the primary transportation routes across the country. Now families could drive themselves, at their own pace. A movement after World War II to “rediscover America” prompted many to abandon the two-to-three-week long vacations in one place in favor of road trips. Families could now see as many sites as they wanted, traveling in the comfort of their own vehicles. While dude ranching declined during this era, tourism boomed in Jackson Hole. Motels became the new wave of the future, and the town of Jackson saw an increase in overnight visitors.

The allure of the Tetons continues to draw people to the valley today. The valley’s recreational opportunities and abundant wildlife are rivaled by few other places in the country. Several dude ranches still operate, continuing to host guests from out of state, and around the globe. Others prefer to camp, or stay at one of many upscale hotels. While the valley looks different today than it did to its original inhabitants, or to the homesteaders, the history and heritage of these groups is not lost.

Tetons rising above the valley floor. Photo by Samantha Ford

ADDITIONAL LINKS

For more information on the Motels and tourism in Jackson, please follow this link:

https://historyjackson.wpengine.com/on-the-trail-of-teton-countys-historic-tourist-accommodations/

Text by Samantha Ford, Director of Historical Research and Outreach