1915: Stephen Mather and his assistant, Horace Albright first travels to Yellowstone National Park to survey how it was run. On a whim they decided to travel south to look at the Teton Range and Jackson Hole. Both men are awe-struck by what they found, a sparsely settled valley bordered by the rugged Tetons. The valley leaves a distinct impression on Albright, who sees the modest homesteads as the beginning of larger developments. He becomes convinced that an expansion of Yellowstone is the only solution to protect the valley.

1919: Horace Albright becomes superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, a position he fills until 1929. One of the biggest goals of his career is to federally protect the Jackson Hole valley.

1926: John D. Rockefeller Jr. comes out to Yellowstone to tour the park with Horace Albright. Albright sees this as an opportunity to invite Rockefeller to become involved in an impending plan to save Jackson Hole and the Tetons. Stephen Mather orders Albright to refrain from speaking about the matter, as Rockefeller is intending this trip to be a vacation only. Rather than letting the opportunity slip through his fingers, Albright risks his career and asks Rockefeller if he would like to see the beautiful valley just to the south of Yellowstone. Rockefeller agrees and is astounded by the beautiful views of the Tetons, and the valley below them. Albright passionately explains that they valley is under threat and in need of financial support to stave off future developments. Rockefeller is intrigued and thanks Albright for the tour. Rockefeller returns home thinking about Jackson Hole and the few struggling homesteads dotting the valley.

-Rockefeller was already known for his philanthropy, he had purchased and donated the land that later became Acadia National Park in Maine in 1916.

1927: Rockefeller is on board with Albright’s ideas and establishes the Snake River Land Company to begin purchasing large amounts of land from the valley residents. Rockefeller’s friend and business partner, Vanderbilt Webb, is made the President of the Snake River Land Company.

-Harold Fabian is the attorney contracted to oversee the process, and Fabian becomes the Vice President. Fabian moves to Jackson Hole during the summers to make sure everything is running in order. Rockefeller and Webb remain in New York City and receive regular correspondence about the venture. Rockefeller’s name is kept hidden to keep land appraisals low.

-Robert Miller, a Jackson Hole resident and founder of the Jackson State Bank, is hired as a field agent for the Company. Miller was chosen because he could provide a “familiar face” for the negotiations taking place on the ground.

-Meanwhile valley residents are circulating their own petition to approve the creation of a preserve or recreation area to protect the open lands in the valley. Feeling pressure from dropping beef prices, harsh winters and droughts, many ranches are struggling. They worry that a wealthy investor will purchase the valley for future developments. Ninety-seven ranchers signed the petition, owning over 27,000 acres of land.

-Robert Miller’s contract expires and both Miller and the SRLC decline to renew it. Relations between the two parties have degraded due to different ideas about which properties to purchase. Miller wanted to focus on the east bank of the Snake River, where he held many mortgages on homesteads; Rockefeller was more interested in the west bank and the more scenic corridor of the valley. It is thought that Miller may also have discovered the true purpose of the Company and left because was vehemently opposed to a National Park expansion or other federal control of the valley.

-Calvin Coolidge signs two executive orders removing over 1,280 acres of public land in Jackson Hole from future homestead claims. The era of homesteading is effectively ended in the valley.

1929: On February 26 President Calvin Coolidge signs the executive order after congressional approval to create Grand Teton National Park. The first park boundaries include only the Teton Range and the several lakes at the base of the mountains. Jackson Lake was excluded from the early park. Roads are improved and the first visitor services are created at Jenny Lake, on the site of preexisting Forest Service concessions. This is seen as a success to Albright, who still endeavors to protect the entire valley, not just the Teton Range.

1930: Rockefeller makes his role in the SRLC public, and the backlash is immediate and angry. Valley residents were offended that outsiders had been secretly stepping in and effectively buying the power to decide what would happen to the future of their valley. Many had few financial interests outside of their lands and homesteads, which had already required backbreaking work to obtain from the federal government. The thought that their hard-won lands could so easily be given back to the government infuriated many, even those originally in favor of selling their lands to help preserve the valley.

-Rumors spread wildly, some were blatantly false and others may have been based in some truth. The truth didn’t matter to many, only that they had been lied to and that they had little say in what happened to the land they loved so much. Though clearly not true, some even suggested that Rockefeller and the National Park Service had partnered to illegally purchase the lands in Jackson Hole.

1933: United States Senate subcommittee meetings are held to determine the legality behind the purchases that were made by Rockefeller and the Snake River Land Company. Suspicions of illegal behavior are proved unfounded and the purchasing schedule is allowed to resume. The testimony of Robert Miller is telling; he claims that he had no knowledge of the true intentions of the Company or of any National Park Service involvement.

1940: Plagued by bad press, the Snake River Land Company is absorbed and rebranded as the Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc. It is hoped that the new name can soften the image of the company and help to create renewed interest in supporting the protection of the valley from future development. The 35,000 acres that Rockefeller has already purchased have so far been passed over by the National Park Service, continuing to be too controversial to be accepted as a donation. It was at yet unclear what would become of the land; an expansion of Grand Teton or Yellowstone or something else entirely?

1943: After decades of frustration, and a refusal from Congress to accept the lands, Rockefeller serves President Franklin Roosevelt an ultimatum: accept the donation of the lands he has purchased, or they will be sold to the highest bidder. Roosevelt acquiesces and by executive order and the Antiquities Act of 1906, creates the 210,000 acre Jackson Hole National Monument.

-Valley residents and State of Wyoming representatives alike vehemently oppose what they see as the over extension of the federal government in creating the Jackson Hole National Monument. Several measures were undertaken by the State of Wyoming to abolish the monument, concerned that it will be a detriment to both the county and state’s economy. President Roosevelt, however, vetoes the bill that would have dissolved the monument. Incensed, the State of Wyoming files a suit against the President. The presiding judge “declined to comment” on a disagreement between the executive and legislative branches of government.

-As a result of 130,000 acres of Teton National Forest land transferring to National Park Service hands, the Forest Service was also against the newly formed National Monument. With little power to change these events, the Forest Service resorted to questionable actions in vacating their ranger stations, forcibly removing the fixtures and some buildings. These actions resulted in severe damage to several buildings, and the removal of the current Forest Service Supervisor to a different agency.

-The Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc. (formerly the Snake River Land Company) opened the Jackson Hole Wildlife Park in the open flats south of Oxbow Bend. This was an attempt to increase tourist numbers by ensuring they would see wild animals. Prior to the homesteaders settling the valley, the bison herds that once roamed the open spaces had disappeared. This new Wildlife Park offered tourists with a glimpse of animals that had not been seen in the valley in decades. Despite being popular, viewing elk and bison behind fencing was abhorred by valley residents like Olaus Murie. This was not how “wildlife” were meant to be viewed and appreciated. In a happy accident, a few of these captive bison would escape their enclosure and start the wild herds that roam the valley today.

1950: At the close of World War II, there was a movement to rediscover the country. Families were looking for ways to reconnect and move on, and vacations were the perfect opportunity to do so. The Jackson Hole valley was quickly becoming the gateway to Yellowstone National Park. With more visitors than ever before, opponents of the national monument were willing to compromise and leave the controversy behind. It would seem that the economy could be boosted from tourism, and much of the valley’s focus shifted to this purpose. On September 14, the Jackson Hole National Monument and Grand Teton National Park were combined to create a 310,000 acre expanded Grand Teton National Park. The life leases held by homesteaders and all concession licenses were now officially held by the National Park Service.

-The original opponents to the Jackson Hole National Monument had one small piece of success in the expansion of Grand Teton National Park. Included in the legislation for the expansion, a new law was added limiting the President’s power to create national monuments, specifically in Wyoming. To this day, Wyoming is the only state where a President cannot create a national monument (over 5,000 acres) without the approval of Congress.

-The new park expansion also resulted in a decision by several more residents to sell their ranches, this time to Grand Teton National Park. Today, about 100 inholdings with around 950 acres remain on private land.

Also see: Homesteading, Cattle Ranching, Dude Ranching and Tourism

Text by Samantha Ford, Director of Historical Research and Outreach

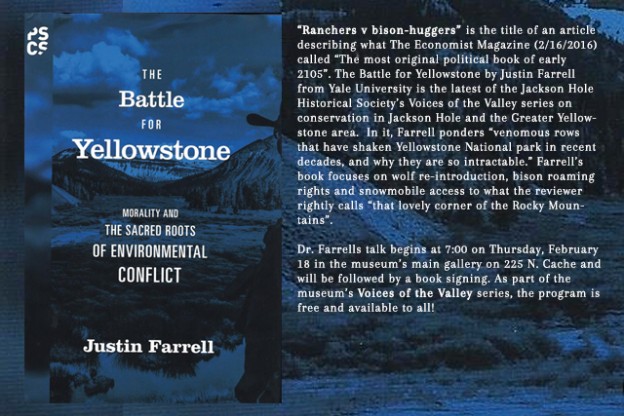

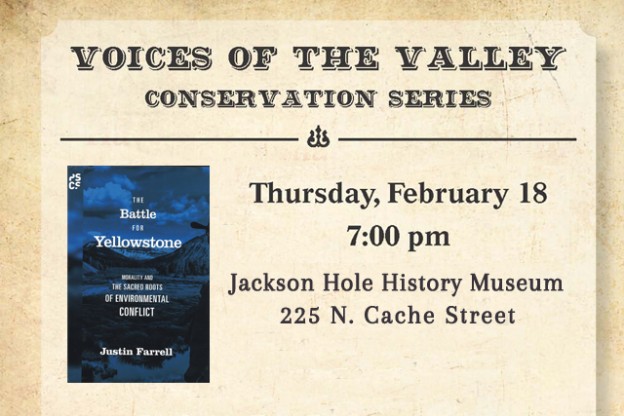

“Ranchers v bison-huggers” is the title of an article describing what The Economist Magazine (2/16/2016) called “The most original political book of early 2105”. The Battle for Yellowstone by Justin Farrell from Yale University is the latest of the Jackson Hole Historical Society’s Voices of the Valley series on conservation in Jackson Hole and the Greater Yellowstone area. In it, Farrell ponders “venomous rows that have shaken Yellowstone National park in recent decades, and why they are so intractable.” Farrell’s book focuses on wolf re-introduction, bison roaming rights and snowmobile access to what the reviewer rightly calls “that lovely corner of the Rocky Mountains”.

“Ranchers v bison-huggers” is the title of an article describing what The Economist Magazine (2/16/2016) called “The most original political book of early 2105”. The Battle for Yellowstone by Justin Farrell from Yale University is the latest of the Jackson Hole Historical Society’s Voices of the Valley series on conservation in Jackson Hole and the Greater Yellowstone area. In it, Farrell ponders “venomous rows that have shaken Yellowstone National park in recent decades, and why they are so intractable.” Farrell’s book focuses on wolf re-introduction, bison roaming rights and snowmobile access to what the reviewer rightly calls “that lovely corner of the Rocky Mountains”.