Author Archives: Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum Web Administrator

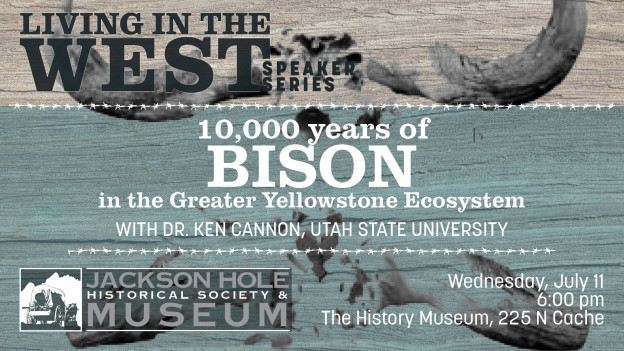

Living in the West Speaker Series

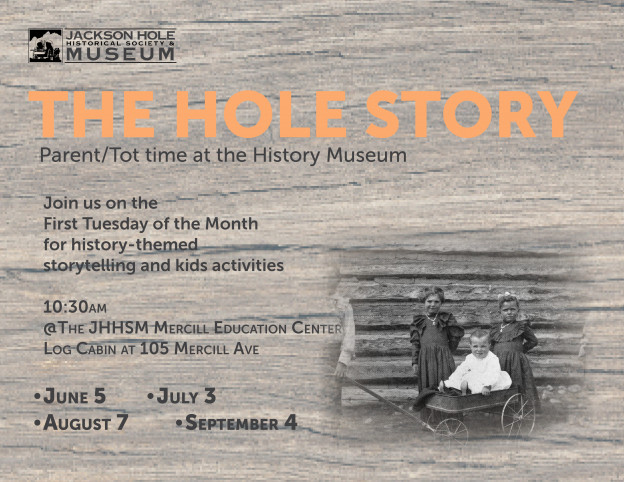

Storytime at the History Museum!

Wolff Ranch

- Marie and Emile Wolff with son Willie at their Elk homestead. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

- The Wolff Ranch. Photo by Samantha Ford.

- The Wolff Ranch. Photo by Samantha Ford.

- The Wolff Ranch. Photo by Samantha Ford.

In 1870, Emile Wolff emigrated from his native Belgium to the United States. He enlisted in the Army, and was stationed at Fort Hall in Idaho. During his service he ventured into Jackson Hole to deliver supplies to the doomed Lt. Gustavus C. Doane* expedition. Despite the foul winter weather, Wolff was impressed by the small valley. Upon his discharge, he began homesteading in Teton Valley, Idaho. Here he became involved with another infamous Jackson Hole story, still told around the campfire. He made the acquaintance of four other German immigrants, one of whom had gone to school with Wolff. The four men were inquiring after supplies they needed for gold panning on the Snake River in Jackson Hole. Wolff directed them towards a neighbor, and wished them luck. Later that summer, Wolff was about to begin haying when he was startled to view a man on foot coming across his fields. Horses were the primary mode of transportation, so the approach was unusual, but not unheard of. When the figure got closer, Wolff recognized him as John Tonnar, one of the four gold prospecting Germans he had encountered earlier in the year. Wolff was surprised to see Tonnar again, who asked for work and a place to sleep. Acquiescing, Wolff asked many questions about Tonnar’s former partners and got only “unsatisfactory” answers. There was plenty of work to be done with haying, and Wolff was more glad to have the assistance rather than question Tonnar’s unusual manners.

A month later, a sheriff and a posse came upon Wolff at home while Tonnar worked out in the field. The sheriff informed Wolff that they had found Tonnar’s three partners murdered and buried under rocks in the Snake River. Wolff was aghast that he had harbored a man capable of murder, and sent the posse into the field after Tonnar. He was captured and brought to court, while Wolff was sent to identify the bodies. After a confirmation that they were the same men Tonnar had been with earlier that summer, a trial in Evanston began. Despite all of the evidence stacked against him, Tonnar was acquitted. It was determined that due to no witnesses, the evidence was only circumstantial. Tonnar then disappeared, and many theories abound as to his guilt and his future. Today, the bend of the River where the three men were discovered is known as “Deadman’s Bar.” Despite these events, Wolff packed up and moved to Jackson Hole where he homesteaded along Flat Creek, adjacent to the Robert Miller homestead. Miller was another character whose reputation is larger than the man. His reported early involvement with local outlaw Teton Jackson and later involvement with John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and the Snake River Land Company cause a lot of disagreement over his true intentions. He did open the first Bank of Jackson Hole and his wife, Grace, was Mayor for several years.

Finding success on Flat Creek, Wolff began looking for a homestead that was farther from the bustle of town. After lands opened up along Spread Creek, in the northern half of the valley, Wolff jumped on a homestead claim. Just south of the future Elk Ranch, Wolff had quality land and easy access to water. He dug a ditch from Spread Creek himself, and received a patent for his homestead in 1906. Prior to this, he briefly returned to Belgium in order to find a wife and married Marie Bettendorff in 1893. Despite their advantageous location, the Wolff Ranch was run within the limits of the original 160 acre homestead. The Wolffs were rare in the valley in that they were successful, but not looking to expand. They also never sold out to their neighbors on the Elk Ranch who expanded quickly. When the Snake River Land Company came knocking in the 1920s, the Wolffs declined the offer to sell. It was obvious that they took great pride in their home, and maintained a modesty that would continue to define the property. To bring in more cash, Marie operated the Elk Post Office for 17 years and Emile sold furs that he trapped. He would also become one of the first Forest Rangers in the valley.

In 1913, Emile Jr. was born in Luxembourg (Marie made sure her children were born in Belgium to ensure their qualification for an inheritance from her family). This proved more expensive in terms of travel than the final inheritance that came their way. Emile, Jr. was better known by the family as “Stippy.” He attended the local school at Elk, and assisted with various ranch chores. In addition to his formal schooling, he began violin lessons at the age of seven. His mother was a skilled singer, and his father had acquired the old piano from John Sargent’s Merymere in Moran. The family became known in the valley for their talent and often played at the many community gatherings. Despite loving the ranch, and the life that came with it, Stippy was never much of a rancher. After his father’s death in 1928, he continued to live on the ranch and assist his mother with chores but he earned a living working odd jobs throughout the valley.

Stippy’s decision not to become a full rancher was probably due in part to the fact that the family’s small 160 acre property was unable to produce much cash flow as the operation so small. Now in the 20th century, cash and business acumen were increasingly in-demand. The family continued playing music at nearly every dance hall and dance event around the valley. In the 1930s offers by visitors and area officials to purchase the small ranch were vehemently rebuffed by Marie Wolff. The family held no official stance on the subject of park expansion or federal government involvement, probably due to their ranch being located on the eastern boundary of Jackson Hole. Despite being adjacent to the Elk Ranch, which was run by the Snake River Land Company, the Wolffs head fast to their land.

In the 1940s, many changes would continue to form the Wolff Ranch. Stippy married Beryl Adams and in 1941, they were deeded one acre from Marie on which to build their house. During World War II, Stippy was called away to work in defense construction. When he returned, the ranch was transitioning away from running cattle to hosting tourists. With the majority of the valley now protected under the Jackson Hole National Monument, grazing options were limited and beef prices were no longer sustainable for such a small ranch. During this time dude ranching and extended family vacations out west were highly desirable. With the majority of Europe recovering from the war, many Americans were turning their sights inward to celebrate the beautiful spaces their own county had to offer. The valley had a long history of dude ranching, and by the 1940s this had evolved into shorter stays and looser requirements for guests. Prospective guests no longer had to request a letter of recommendation from a mutual friend of the ranch owner, nor did one have to provide references on the personality of their family. The Wolffs saw an opportunity to offer small overnight cottages, offering the advantage of overnight stays. The rest of the valley was transitioning away from the traditional weeks-long dude ranch stay to accommodate families who wanted to see and do as much as possible. The construction of U.S. Highway 89, the Wolff Ranch was now directly on of the main transportation routes in the valley.

In 1954, Marie Wolff died and the property passed to Stippy, his brother Willie and two sisters. They expanded the small motor court (as they were called, a small circle of cottages with parking out front for automobiles) and added a gas pump. The old main ranch house became a dining room and kitchen. Stippy and Beryl ran the majority of the business, with Beryl having the primary responsibility. The family business continued to be popular until the 1970s when small roadside motor courts were declining in favor of large hotel-based resorts. The construction of the Jackson Lake Lodge and Colter Bay campground near Moran drew a lot of the Wolffs’ former clientele away. In 1978 Stippy and Beryl sold the ranch to the National Park Service in return for a lease that would terminate on December 31, 1999. Sadly, in 1988 Stippy would meet an early death in a logging accident, and Beryl remained on the property for only a year after that. The winters were becoming difficult to bear, and she spent most of her time in town. In another twist of fate, she died on January 3, 2000 only days after the lease had ended and the property formally transferred to Grand Teton National Park.

*Doane had commissioned the expedition hoping to become famous. Despite the Snake River having already been surveyed, Doane was seeking the fame of the earlier Hayden expeditions. His hubris caused him to overlook details like bringing enough supplies for the rugged terrain and underestimating the harshness of winter. The expedition nearly starved to death and required rescue and immediate recall to Fort Ellis.

Text by Samantha Ford, Director of Historical Research and Outreach

Digging into the Past: Family Fun

Hunters of the High Mountains

Jackson Hole & The President Arthur Yellowstone Expedition of 1883

President Chester A. Arthur Photograph by Charles Milton Bell

By all accounts, Chester Arthur (1829-1886) was an accomplished angler, adept at both bait-casting and fly-fishing. He had tested northern waters in Canada and those of the American South in Florida. Salmon, trout, and bass had all filled his creel. Indeed, throughout most of his life—as lawyer, New York “machine” politician, and President of the United States—Arthur found solace and relaxation in plying various waters with line and reel . In 1883, as the sitting President of the United States, he journeyed on the fishing trip of his lifetime, one still cherished and sought after by many people throughout the world—a visit to the world-class wonders and trout streams of Yellowstone National Park.

Arthur’s presidential visit to the beauty and wonders of America’s first national park was no mere vacation from the duties of office. Instead, myriad back stories swirled around the trip, dealing with diverse matters such the state of Arthur’s health; the issue of how to stay in touch with Washington while roaming the wilderness; the interplay of commercial and conservation interests about the park itself; and of course, the niggling details of the journey and who would be the president’s companions.

Jim Bridger spread along the Snake, Green, Wind and other rivers

The President’s health concerned people since he had grown thinner and seemed weaker two years into his presidency. (Arthur became president when James Garfield, who actually won the presidential election of 1880, was assassinated 1881. As the sitting Vice-President, Arthur inherited the office). A very private man, Arthur tried to keep news about his health from the public eye—he suffered from Bright’s disease, which impacts the kidneys. In an attempt at rejuvenation, he vacationed in Florida in April 1883, but suffered an attack of intense pain and returned to the capitol. Subsequent public appearances seemed to confirm his weakened condition. So when it was announced later that year that he intended to travel to Yellowstone, running debates emerged in the country’s newspapers about the wisdom of undertaking such a rigorous adventure.

Some papers derided the President for leaving the country without a leader (since there was no vice-president) to take his fishing “junket.” Others rallied to his support, suggesting that fresh air and fishing could alleviate some of the stresses demanded by his office. Still others, including the influential conservation-oriented journal, Forest and Stream, and its editor, George Bird Grinnell, hoped the trip would shed light on the management of the park and spur efforts towards more conservation of park lands and animals.

At the heart of the matter, at least for many people, was the management of the park. In the time since Congress created the park in 1872, a little over 8000 people had visited during the summer months to see its wonders. But as much as they were enthralled with the vistas and wildlife of the park, the visitors often left detrimental marks on the lands and animals. Hunters poached game at will; loggers cut down thousands of trees to build structures within and without the northern boundaries; a spur line from the soon-to-be-completed Northern Pacific Railroad sought access to bring fare-paying tourists into the park; and various commercial vendors sought leases to build hotels and other permanent structures. Moreover, roads were haphazardly planned and implemented; while newspaper reporters, businessmen, and politicians debated the merits of park expansion, game management, commercial development, law enforcement, and oversight of the national treasure that was Yellowstone. Many of the visitors also chipped away at the multihued rock ledges at the borders of geysers or carved names or initials into trees and rock outcroppings. Others delighted at tossing tin cans or other trash into geyser pools to watch them be ejected during eruptions.

These issues were not totally new. The region that encompassed what would become Yellowstone Park had long been part of the American story of westward expansion. But focus on Yellowstone by the U.S. government was relatively recent as were commercial mining, timber, and hunting interests. White Americans first heard about the wonders of the land when tales told by fur trappers John Colter, Jim Bridger (1804-1881) and others reached American readers in the early 1800s. Of course, American Indian had been using the area’s resources for perhaps thousands of years. Sheep Eater Indians actually lived in the heart of the park. Collectively, the Sheep Eater Indians (also known as the Mountain Shoshone) were small and widespread groups who dwelled in the Jackson Hole area, Wind River, Bitterroot and Absaroka Mountains, as well as the Lamar Valley and other regions within present park boundaries. Other groups of Shoshones, whose territories spread along the Snake, Green, Wind and other rivers of present-day Idaho and Wyoming, and also the Lemhi Indians of north central Idaho, frequented the area. So did Crow and Blackfeet Indians from the north. Nez Perce Indians knew its treasures. At one time, so did Kiowas. Northern Arapahos and Northern Cheyennes occasionally came into the region from the east.

William F. Raynolds

White expeditions really did not get underway until the 1860s, although it is believed that individual whites visited the area nearly every year beginning in 1826. The first organized exploration, led by Captain Willam F. Raynolds (1820-1894) and guide Jim Bridger, took place in 1860. But Bridger was unable to retrace his earlier steps into the heart of Yellowstone’s geological wonderland. Private citizens from Montana explored the Lamar Valley and saw Yellowstone Lake in 1869. This led to another joint military and civilian expedition the following year, headed by General William Washburn (the surveyor–general of Montana), Lieutenant Gustavus Doane (1840-1892), and Nathaniel Langford (1832-1911). Langford had ties to Jay Cooke, a principal investor in the Northern Pacific Railroad. Cooke could see the commercial potential for increased railroad profits from exploitation of Yellowstone, and agreed to back the expedition. The reports of the various men in this group spurred the initial interest by Congress in creating the national park.

Gustavus C. Doane, taken about 1870

Nathaniel P. Langford, about 1870

What “sealed the deal,” as far as creating the park, came about as a result of the Hayden geological survey in 1871. Painter Thomas Moran (1837-1926) and photographer William Henry Jackson (1843-1942) joined Ferdinand Hayden’s (1829-1887) geological survey team, sponsored by the government. Their art helped inspire Congress to create the park and certainly inspired readers of the national presses and journals that published their work in their pages.

President Ulysses Grant (1822-1885) signed the bill into law on March 1, 1872, and Yellowstone entered the public arena as the first national park.

The law creating the park, however, provided few rules, regulations, and no funding. Congress did not appropriate any money to support park operations, including salaries of the superintendents, until 1878. Nathaniel Langford served as the first superintendent from 1872 until 1876, but only visited the park a couple of time during his tenure. He was followed by Philetus Norris (1821-1885), who was on duty when Congress finally funded a budget for the park in 1878. Matters were not helped because a succession of six men served as Secretary of the Interior between 1872 and 1876.

Thomas Moran, about 1890-96, by Napolean Sarony

Wm. H. Jackson as a young man

Although the Interior Department oversaw Yellowstone Park, differences of opinion in park management often characterized relations between the secretaries and their superintendents, especially in matters of commercial development, concession leases, controlling hunting and timber activities, etc. The military presence in Yellowstone that began in 1870 was essentially due to one man: General Philip Sheridan (1831-1888).

Ferdinand Hayden about 1870

When Ulysses Grant took office in 1868, Sheridan became the top army officer for military affairs in the West. He encouraged the various expeditions and surveys in order to gain familiarity with western territories and the American Indians who laid claim to those lands. Once Indian warfare subsided, Sheridan’s interest in Yellowstone turned personal. He made back-to-back trips into the park in 1881 and 1882. These trips turned him into an advocate for the care and maintenance of the park. His report on his findings about park conditions found the eyes of Senator George Vest (1830-1904), who sat on the Senate Committee on Territories. Vest, from Missouri, was first elected in 1878 and prior to receiving Sheridan’s report, was not known to have any interest in Yellowstone. But Sheridan’s findings galvanized Vest into action and he became a staunch supporter of the park. Their agenda included three basic components: to expand the area of the park on the eastern and western borders; to reduce the power of the Secretary of the Interior to award commercial leases and concessions without congressional oversight; and to protect the geological formations and wildlife of the park from vandalism and hunting.

U.S. Grant, mid-1870s

Philetus Norris as a trapper

Thus, Sheridan’s invitation to President Arthur to try his hand at fishing Yellowstone’s waters almost certainly included hopes that Arthur might take up Yellowstone’s cause. Sheridan arranged all travel arrangements, security details, and communications for the presidential party. Because Arthur loathed newspapers and their reporters, no reporter traveled with the group. Instead, Sheridan used the cavalry to transport the official daily messages released to report on the President’s progress.

Washakie, c.1883 by Baker & Johnston

In addition to Arthur, Sheridan, and Vest, the traveling companions included Secretary of War Robert Lincoln (1843-1926, son of President Abraham and Mary Lincoln), who had been on the 1882 trip into the park with Sheridan; Montana Territorial Governor John Crosby (1839-1914); Daniel Rollins (1842-1897), friend of Arthur and a surrogate (probate) judge in New York; General Anson Stager, (1825-1885), an officer in Western Union telegraph company; Lieutenant Colonel Michael Sheridan (1840-1918), brother to General Sheridan and placed in charge of writing the daily communication reports; Major William Forwood (1838-1915), surgeon, who had traveled with General Sheridan on the previous Yellowstone expeditions; Captain William Clark, a staff member to General Sheridan; Lieutenant Colonel James Gregory, responsible along with Michael Sheridan for the daily reports; and George Vest, Jr., the son of Senator Vest. Each was responsible for paying for his own food and providing his own clothing and fishing/hunting gear.

Black Coal, 1882 by John K. Hilliers

Robert T. Lincoln, by Harris & Ewing

One other person also joined the party at the request of General Sheridan: Frank Jay Haynes (1853-1921), a young photographer. Haynes operated a photography studio in Fargo, North Dakota, and had been hired the previous year to photograph Yellowstone’s features the previous year by the Northern Pacific Railroad (NP) as part of its advertising campaign to entice tourist to visit the park via the NP. Sheridan had met Haynes on the 1882 trip to the park and was impressed with what he saw. While Arthur and Lincoln nixed the idea of reporters traveling with the company, they agreed to have a photographer record their activities. The only restriction placed on Haynes was that he not photograph the President while he was fishing, although he was free to photograph the President’s catch.

George G. Vest

F.J. Haynes, 1880

The presidential vacation began with a week-long railroad trip to Green River, Wyoming. A few stops were made along the way, most notably in Chicago, but for the most part, the President sped through the country. After an overnight stay in Green River, the “real” vacation began on August 6. A two-day journey via “spring wagons” covered the 150 miles to Fort Washakie to join with the larger military escort and with photographer Haynes. President Arthur often preferred to ride on top with the driver during this portion of the trip. At Fort Washakie, the headquarters of the Wind River Indian Reservation, the Shoshone and Arapaho Indians performed a sham battle scene and also danced for the group. Arthur met with the two head chiefs of each tribe, Washakie (c. 1804/1810-1900) of the Eastern Shoshones and Black Coal of the Northern Arapahos, to discuss plans concerning dividing the reservation into individually assigned allotments. Both leaders resolutely informed the President that they did not want to see the reservation allotted, a stance they maintained throughout their lives.

On August 10th, wagons were left behind and the President and his party continued on horseback, basically following the route taken by General Sheridan the previous year. At each camp, Arthur and Senator Vest vied for top fishing honors. Others also tried their hand at mending lines; some hunted game. But in accord with his views about conservation of wildlife, General Sheridan ordered than there would be no sport hunting. Game kills were for food only. Once they actually entered the park, Sheridan banned all hunting activity.

For the next three weeks, President Arthur enjoyed what present-day tourists term a guided horsepacking trip. In modern times, licensed guides lead hunters and fishers on such adventures in many western states. In the President’s case, his guide was the highest ranking officer in the western division of the U.S. Army. Just as in today’s guided trips, Sheridan’s troops set up tents, cooked the meals, washed clothes, and otherwise insured the comfort of the “VIPs” as best they could in a wilderness setting. Approximately two weeks were spent riding northward to reach the park boundaries, with one week traversing the park and exiting near Mammoth Hot Springs. Then the President again boarded a train, headed to Chicago for a few more brief meetings, and then seated himself again in the Oval Office.

Anson Stager

Wm. H. Forwood

By all accounts, everyone enjoyed themselves immensely, but Arthur did not join the conservation bandwagon. Nevertheless, the trip helped General Sheridan and Senator Vest clearly state their case for conservation, preservation of wildlife, and review of concessions and leases. In the aftermath, new directives and regulations emerged that helped define the purpose and maintenance of Yellowstone National Park and others created in its wake. This did not take place immediately; indeed, Yellowstone was transferred to military oversight and control in 1886, not to be returned to the Interior Department until 1916 and the creation of the National Park Service.

Haynes’s photographs perhaps were the real success of the expedition. Although he did not bring enough glass plates to record all the details he wanted, he used his images taken the year before and on a return trip in 1884 to bolster his reputation as the premier photographer of Yellowstone Park. His studio received hundreds of order for prints, and that same year used his contacts gained in 1883 to secure a photography concession for the park. He held that position until 1916, turning over the job to his son, Jack Ellis Haynes (who remained the photographer in Yellowstone until 1962). The printed work of the Arthur expedition, A Journey Through the Yellowstone National Park and Northwestern Wyoming 1883 contains images that still remain icons of Wind River, Jackson Hole, and of Yellowstone photography.

For images of the entire expedition, click here

Support JHHSM at Old Bill’s Fun Run

Thank You Petticoat Rulers! Cissy Patterson Opening